Fundamental Strategic Priorities to Managing Valuable Ocean Resources, Backed by On-Site Experience

Access to data and information is key to better management.

Back in 2008, I used to provide IT services to producers and exporters of fishmeal seafood in Latin America. I was very impressed by the amount of data they worked with, and the high-level of engineering and technical expertise engaged in these companies. At the time, actively working in this sector enhanced my understanding of the different seafood supply chains and of the different sourcing relationships, both industrial and artisanal. A few years later, I moved to San Francisco, which catapulted my experience and direct program design and implementation within the seafood sector in 14 additional countries. This experience gave me a more comprehensive understanding and holistic picture about the role of seafood net-importing countries, such as the United States. This made me think differently. I realized that pressure from importing countries is not always the path to success.

Focusing on the quality and validity of seafood-production-data will bring all the actors involved in the fishery closer to adequately manage seafood resources.

Consider industrial fisheries who have the best fishing infrastructure on the planet. Some are working very well with highly qualified staff, abiding by all the regulations imposed on them. The problem is not the capacity of industrialists to comply, it is the quality and validity of the data at their disposal and how they use them for decision making.

The key to the adequate management of the ocean resources is not just generating data, it is generating the right data.

There is a notable distinction between data generated by traceability and that generated by verification. Having traceability does not always necessarily mean that one is able to manage ocean resources properly. Despite what some might believe, managing ocean resources adequately is less about measuring and more about creating the conditions and obtaining the necessary data for more seafood abundance. Also, it is about learning how to create less interaction with bycatch and, thus, share the benefits of these delicious renewable resources which can feed the planet adequately.

Here, there are 5 lessons I have learned to manage ocean resources better.

1. Government access to data and private sector data providers.

Have you ever looked into a government seafood database? Few are impeccable, others simply do not exist, or they are of extremely poor quality. At the speed of technological development, Governments must set clear rules and data protocols which are urgently needed by third party companies to contribute to collect and enhance “verified data generation”. Often, government fisheries statistics departments have outstanding professionals trying to make headway with underfunded budgets and lack of political support. Management thinker Peter Drucker is often quoted as saying that “you can't manage what you can't measure”. What Drucker means in the seafood sector is that you cannot know whether you are successful in ocean management unless a given notion of success is defined and tracked (objectives, goals, targets…). The first steps in the right direction for Government fisheries programs is to provide the institutional and financial framework to establish a clear database structure--with an accompanying published API. The strategic aim is to provide clear guidelines for the interoperability of different systems out there that, now, do a good job of obtaining adequate data.

Did you know that:

- Chile has developed the first API in Latin America for interoperability of third-party applications for data?

- Ecuador is implementing a scalable electronic reporting process increase control capacities and support the work of inspectors?

- The Department of Natural and Environmental Resources of Puerto Rico has electronic reporting data data from ~700 of their current ~800 fishers registered as having the appropriate technology?

2. Determine the right mix of observers and electronic monitoring equipment.

Covid-19 is bringing this issue to the forefront of seafood fisheries monitoring. Who wants to bring somebody onboard who could be sick! Though observers play an important role in large vessels, scientific sampling and monitoring, medium and small vessels have major issues with the current pandemic. Remote electronic monitoring can play an extremely useful role in complementing an observer's work, and in some cases can replace them completely. If we want to create a strong case for adequate and responsible fishing, we need to focus on the specifics of each fishery and their respective fishing gears, to create clear verification protocols and iterate on best practices until zero bycatch is achieved.

3. Start using your monitoring data for marketing

The largest industrial players are very well equipped with vessel monitoring technologies. Most are making strong efforts to comply with quotas, have strict reporting, and have added additional layers of certification to make sure things are done right. If you are so good at providing data, you can most definitely use this asset to share the good work you are doing with your clients. There are countless research studies that can offer insight on using your data for optimizing your marketing strategic objectives and goals. Giving more seafood-sourcing-data to your customer can help any company to gain more value from their engagement and have a better experience with any brand on the market. This type of customer-oriented marketing will increase retention, create awareness of your customer-base, and strengthen existing customers’ preferences towards future sales.

4. The Great Importance of Small-Scale Fisheries

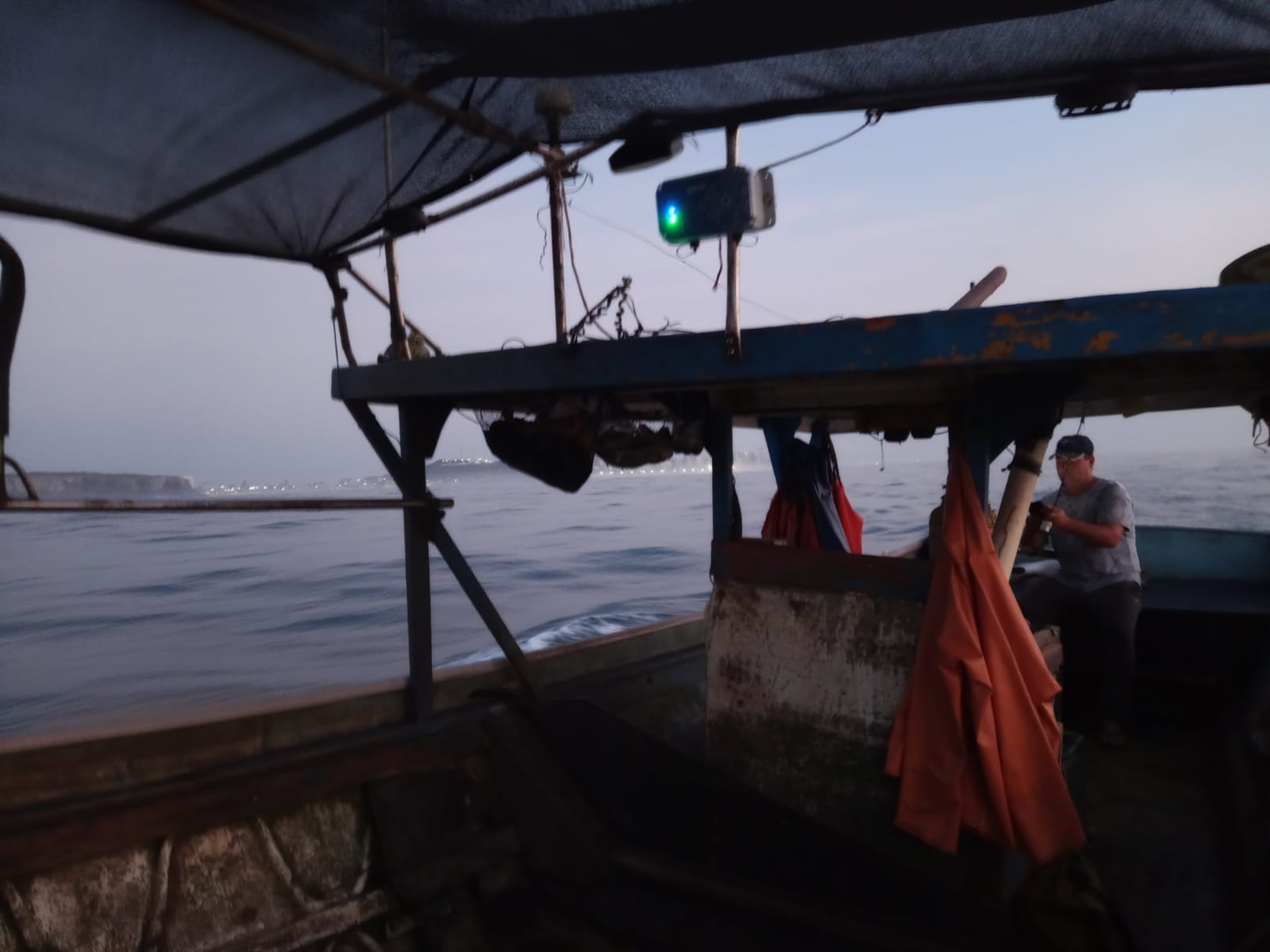

If you want to manage ocean resources properly you must include small scale fisheries. In a large proportion of countries, small-scale fisheries account for more than half of the country's total seafood production. Artisanal fishers are also critical suppliers to industrial exporters. In all the countries I have worked in, experience shows that the actors who have the most data are those that are involved as “intermediary players”. These players fill out electronic or paper-based forms, which contain very valuable data and information to manage from extraction onto the final consumer. Small scale fishers are left completely out of the equation and almost no verification of fishing practices take place. For Government Officers and Inspectors who are devoted to fishery’s management, the small-scale sector has always been a headache. Lack of funding and a human centered inspector-based-monitoring-approach is viewed as the only solution. A solution that is completely not scalable. Technology is critical in this space as it can solve the problems that arise from the lack of adequate data, and it may enhance artisanal fishery involvement very quickly. The general perception is that small scale fishers will never accept using verification technology but, experience demonstrates that is completely the other way around. Many artisanal leaders understand the need for creating a more sustainable future for their fishery resources and are prepared to meet the highest standards possible.

5. Local Economies in net seafood export suppliers matter.

The major push for monitoring comes from developed countries (buyers), but very little is done in emerging market economies in managing their national seafood demand. Local market-based initiatives are of critical importance if one is to create a local pull. The power of the market will always create greater end-consumer involvement and would increase the pressure to improve quality and obey standards, so that public policy can accelerate the way ocean resources are properly monitored.

This is not an effort that will yield results overnight. Government, private sector actors and the local research authorities for fisheries need to invest time and weigh in on verified data. It is important to understand that with these players great progress can be made right now to collect, process and disseminate more reliable data, badly needed to manage existing ocean resources more effectively and transparently.