Electronic Monitoring and Reporting as a Single System for Small Island Fisheries

Small island fisheries face a familiar dilemma when considering digital tools

Small island fisheries face a familiar dilemma when considering digital tools: electronic monitoring (EM) promises better visibility at sea, while electronic reporting (ER) improves data quality and compliance on land, yet budgets, staffing, and connectivity constraints rarely allow for parallel systems. As a result, many administrations feel forced to choose one or delay both. Experience from small island contexts shows that this is a false choice. EM and ER work best when designed as one lightweight, integrated system, deployed incrementally and governed under a clear public-sector mandate.

The Reality of Small Island Constraints

Small island states operate under conditions that differ fundamentally from large industrial fisheries: Limited technical staff, Tight and often donor-dependent budgets, Intermittent connectivity,High expectations for transparency and accountability, Long procurement cycles and sensitivity to vendor lock-in, Digital fisheries systems that ignore these realities tend to stall at pilot stage, regardless of technical sophistication.

Why EM Alone or ER Alone Is Incomplete

Electronic monitoring without electronic reporting often results in: High data volumes with limited institutional uptake Manual reconciliation between observation and reporting Increased analytical burden on already constrained teams Electronic reporting without electronic monitoring, on the other hand, relies heavily on: Self-reported data Post-hoc validation Limited visibility into fishing activity itself In practice, observation and reporting are two halves of the same system. When treated separately, both underperform.

A Modular EM + ER Pathway

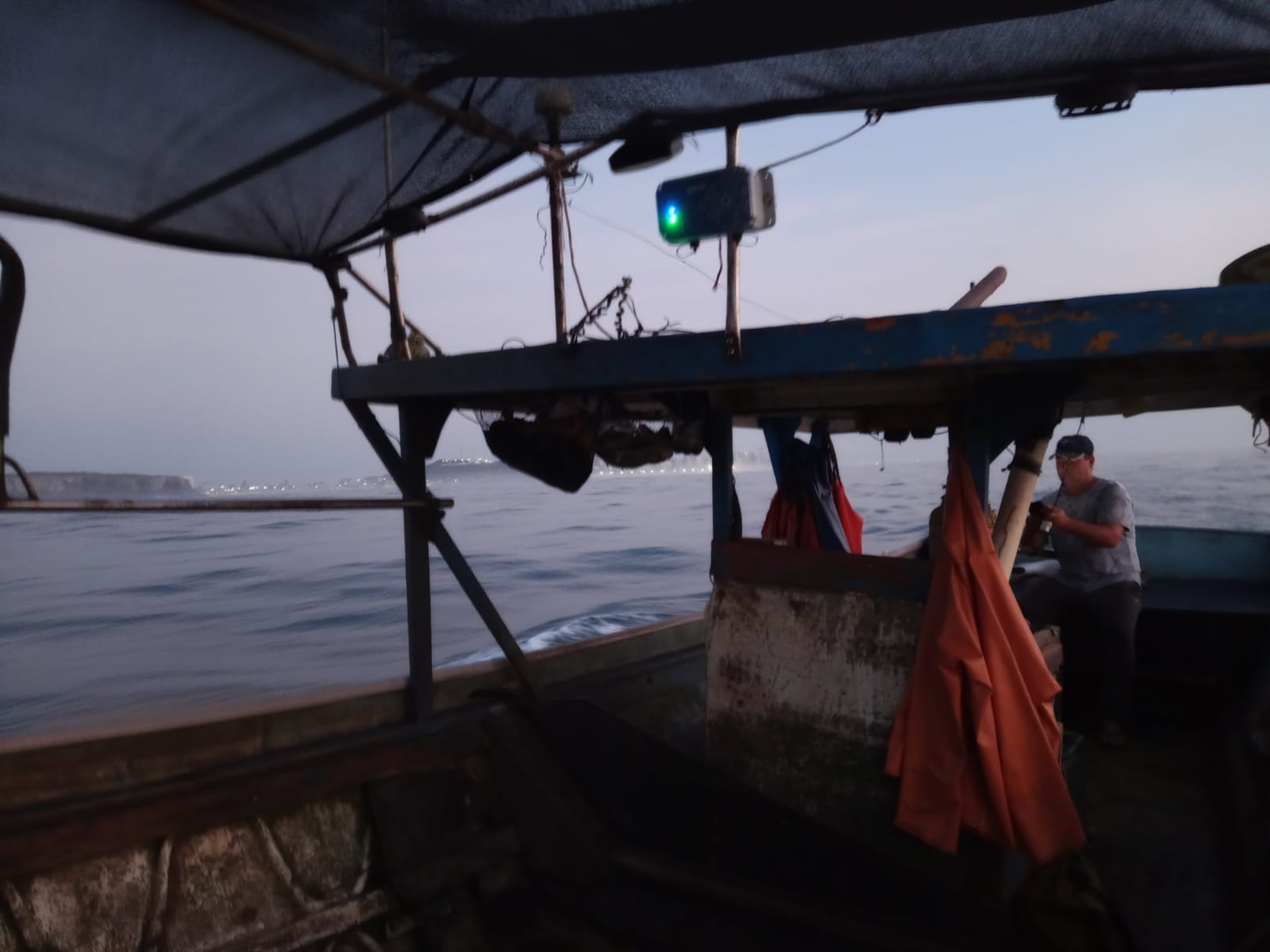

A more resilient approach is to design EM and ER as modular components of a single architecture, allowing countries to: Start with EM or ER, depending on priorities Add the second component when ready Maintain a single data backbone throughout This approach has been applied in small island contexts through complementary implementations: Electronic monitoring deployments adapted to small fleets and limited connectivity, as demonstrated in Barbados Low-burden electronic reporting systems embedded in regulatory workflows, as implemented in Bermuda Each component stands on its own — but together they provide end-to-end visibility from fishing activity to reported catch.

Data Sovereignty as a Design Requirement, Not a Feature

A recurring concern among small island administrations is long-term dependency on external vendors or platforms. For this reason, both electronic monitoring and electronic reporting implementations were designed using an API-first architecture, ensuring that governments retain full ownership and control of their fisheries data. Key principles include: Open APIs to integrate with existing or future national databases Clear separation between data ownership and service provision The ability for governments to self-host or transition systems over time Avoidance of closed, proprietary data structures This approach allows digital systems to strengthen institutional capacity rather than replace it, preserving data sovereignty while still enabling external technical support where useful. Similar principles were previously applied in national-level traceability work in Chile, and have proven particularly relevant in small island contexts where institutional continuity is critical.

What This Enables for Small Island States

When EM and ER are implemented together — and designed for sovereignty from the outset — administrations gain: A coherent, end-to-end view of fishing activity and reported catch Reduced duplication of systems and costs Greater confidence in compliance and enforcement data Flexibility to evolve systems over time without re-starting from zero Stronger positioning in donor-funded or regional initiatives Most importantly, digital systems become infrastructure, not projects.

From Choice to Continuum

The question for small island fisheries is not whether to adopt electronic monitoring or electronic reporting. It is how to design a continuum that: Fits current capacity Preserves sovereignty Allows incremental growth Avoids long-term lock-in Treating EM and ER as parts of a single, lightweight system is one practical way to achieve that balance.